Cosmic Cannibal: The 15-Year Hunt for a Star-Shredding Black Hole

A Crime Scene 450 Million Light-Years Away

In the vast, silent theater of the cosmos, an unsuspecting star met a grisly end. For eons, it had traced its quiet path through the constellation Hercules, a tiny point of light among countless others. But its orbit carried it toward a dark, unseen predator. As it drew closer, the star was ambushed by an immense gravitational force, stretched, and violently torn to shreds. This stellar murder, which took place 450 million years ago, sent a scream of high-energy light across the universe—a cosmic distress call that would take nearly half a billion years to reach Earth. When it finally arrived, it triggered one of the longest and most fascinating astronomical detective stories of the 21st century.

Table Of Content

- A Crime Scene 450 Million Light-Years Away

- Table 1: The HLX-1 TDE Timeline – A Cosmic Detective’s Log

- Unmasking the Culprit: The Black Hole Family’s Middle Child

- Table 2: Black Hole Family Portrait

- The Physics of a Stellar Murder: Anatomy of a Tidal Disruption

- The Bigger Picture: Why We Hunt for Black Hole Leftovers

- References

The first clue was picked up in 2009 by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, a space telescope designed specifically to detect the universe’s most violent and energetic phenomena. Astronomers using Chandra noticed a powerful and unusual flare of X-rays—the signature of matter heated to millions of degrees—emanating from a location where nothing so bright was expected. The source was dubbed HLX-1, for Hyper-Luminous X-ray source 1. This was no ordinary cosmic event. Its energy profile didn’t match that of a typical exploding star, or supernova. This was something different, something more ferocious.

The plot thickened as astronomers kept watching. The source didn’t just flash and fade. Instead, it grew brighter, culminating in a spectacular peak of intensity in 2012, when it blazed roughly 100 times more brightly than when it was first discovered. After reaching this brilliant climax, HLX-1 began a long, slow, and remarkably steady decline in brightness that has been tracked for more than a decade, through 2023. This specific light curve—a sharp rise, a brilliant peak, and a gradual power-law decay—was the key piece of evidence. It was the classic signature of a black hole’s mealtime, an event astronomers call a tidal disruption event, or TDE. It was the sound of a star being consumed.

To solve this cosmic mystery, detectives needed more than just the “sound” of the crime; they needed to see the crime scene. This required calling in a partner: the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. While Chandra had captured the high-energy scream, Hubble’s unparalleled sharp vision in visible and ultraviolet light could pinpoint the flare’s exact location and reveal the environment in which this cosmic catastrophe occurred.

Hubble’s observations placed HLX-1 on the outskirts of a giant elliptical galaxy named NGC 6099, located approximately 450 million light-years from Earth. This detail was crucial. The event wasn’t happening in the galaxy’s center, where a supermassive black hole would be expected. Instead, it was flaring from within a dense, compact cluster of stars about 40,000 light-years from the galactic core. This off-center location was a major puzzle piece, pointing toward a culprit far rarer than the usual suspects.

The investigation into HLX-1 showcases the scientific process in action, where understanding evolves as new data refines the picture. Initial studies between 2009 and 2012 had associated the source with a different galaxy, ESO 243-49, which is closer to Earth at about 290 million light-years. For years, this was celebrated as a landmark discovery. However, with more precise data from Hubble and a longer observation baseline, astronomers were able to re-evaluate the object’s distance and true host. This led to the updated conclusion that the famous X-ray source was, in fact, part of the more distant galaxy NGC 6099. This refinement wasn’t a contradiction but a triumph of persistent observation, turning the investigation into a true detective story where even the address of the crime scene was a mystery that took years to solve.

Table 1: The HLX-1 TDE Timeline – A Cosmic Detective’s Log

| Date/Year | Observatory | Observation | Significance |

| 2009 | NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory | A bright, unusual X-ray source (HLX-1) is detected on the outskirts of galaxy NGC 6099. | The first clue. The high energy points to a black hole, but its nature is unknown. |

| 2012 | Chandra / ESA’s XMM-Newton | HLX-1 reaches peak brightness, flaring to ~100 times its 2009 luminosity. | The climax of the event. This intense flare is consistent with the moment of maximum consumption in a TDE. |

| ~2012-Present | Hubble Space Telescope | Hubble provides high-resolution optical and UV images of the location. | Confirms the source is in a compact star cluster, providing a “food source” for the black hole and supporting the “cannibalized dwarf galaxy” origin theory. |

| 2012-2023 | Chandra / XMM-Newton / Swift | The X-ray source begins a long, slow, steady decline in brightness. | The “smoking gun” for a TDE. This predictable fading is the signature of an accretion disk running out of fuel, distinguishing it from other cosmic events. |

Unmasking the Culprit: The Black Hole Family’s Middle Child

The excitement surrounding HLX-1 stems from the identity of the culprit. This wasn’t just any black hole; all evidence points to it being a member of a rare and elusive class known as intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs), the long-sought “missing link” in black hole evolution. To understand why this is such a big deal, it helps to look at the entire black hole family.

Astronomers generally divide black holes into three categories based on their mass, much like sorting animals by size.

- Stellar-Mass Black Holes: These are the “house cats” of the cosmic jungle. With masses ranging from a few to perhaps 20 times that of our Sun, they are born from the explosive death of a single massive star. If you could see one, it would be about the size of a city. Our Milky Way galaxy is thought to contain as many as 100 million of them, though we’ve only found about 50 so far.

- Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs): These are the colossal “blue whales” of the universe. Weighing in at millions to billions of times the Sun’s mass, these monsters lurk at the center of nearly every large galaxy, including our own Sagittarius A*. The SMBH at the heart of galaxy M87, the first to ever be directly imaged, is 6.5 billion solar masses and so large its event horizon would swallow our entire solar system.

- Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs): For decades, these were the ghosts in the machine. Astronomers saw the small black holes and the giant ones, but a huge gap existed in between. IMBHs, with masses from 100 to hundreds of thousands of times that of the Sun, are the “teenagers” of the black hole family—the crucial missing link between the stellar-mass and supermassive classes.

This “missing link” problem has been a major puzzle in astrophysics. How does the universe build a billion-solar-mass monster? The leading theory is that they grow through a process of “hierarchical merging”—they start small and get bigger by consuming stars, gas, and other black holes over cosmic time. This process requires a population of mid-sized IMBHs to act as building blocks, merging together to form the supermassive giants. But without finding any IMBHs, this theory remained unproven. The discovery of a strong candidate like HLX-1 provides the first concrete evidence that these middleweights really do exist, lending powerful support to our models of cosmic construction.

The backstory of HLX-1 makes it even more compelling. Its location on the outskirts of NGC 6099, nestled within its own star cluster, strongly suggests it is the surviving core of a small dwarf galaxy that was long ago ripped apart and swallowed by the much larger NGC 6099. In this galactic-scale act of cannibalism, the dwarf galaxy was shredded, but its dense central black hole and a handful of companion stars survived. HLX-1 is therefore not just a black hole; it’s a wandering relic of ancient violence, a ghost of a galaxy that no longer exists. The star it was just seen devouring was likely one of the last companions from its long-lost home.

This dramatic origin story also helps explain why finding IMBHs is so challenging. These objects are fundamentally stealthy. They are not massive enough to gravitationally dominate the center of a large galaxy, so they don’t have a constant stream of gas to feed on. They are often isolated, lacking the nearby companion star that would cause a stellar-mass black hole to light up as a bright X-ray source. By default, they are dark, quiet, and nearly impossible to see.

This creates a “feast or famine” situation for astronomers. The only reliable way to find an IMBH is to catch it in the brief, violent act of feeding—a TDE. A TDE is the cosmic equivalent of a flashbulb going off in a dark room, momentarily illuminating the predator. Astronomers can’t just point a telescope and find an IMBH; they must patiently survey the entire sky, night after night, waiting for one of these transient flares to erupt. The discovery of HLX-1’s flare in 2009 was a “feast” moment, providing a massive windfall of data from an otherwise invisible object. As it continues its long fade into obscurity, the “famine” returns, highlighting the critical importance of all-sky surveys and rapid-response observatories in the ongoing hunt for these missing links.

Table 2: Black Hole Family Portrait

| Class | Typical Mass | Analogy / Size | Formation |

| Stellar-Mass | 3 to 20x the Sun’s mass | A “cosmic house cat” / The size of a city | The core-collapse of a single, very massive star in a supernova. |

| Intermediate-Mass (The Missing Link) | 100 to 100,000x the Sun’s mass | A “cosmic teenager” / Could fit inside Earth’s orbit | A huge mystery! Possibly the runaway merger of stars in dense clusters, or the core of a cannibalized dwarf galaxy (like HLX-1). |

| Supermassive | Millions to Billions of times the Sun’s mass | A “cosmic blue whale” / The size of our solar system | Another mystery! Possibly grew from IMBHs merging, or from the direct collapse of giant gas clouds in the early universe. |

The Physics of a Stellar Murder: Anatomy of a Tidal Disruption

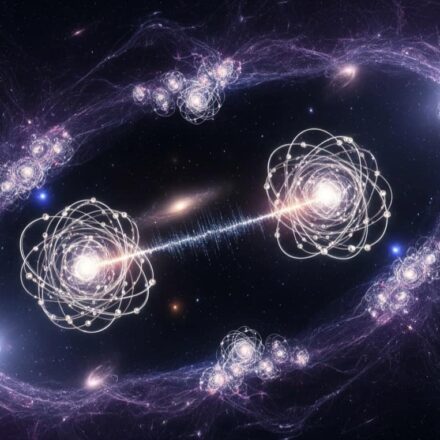

The process by which a black hole destroys a star is a demonstration of gravity at its most extreme. To understand it, we can start with a familiar concept: the tides on Earth. The Moon’s gravity pulls slightly harder on the side of the Earth facing it than on the far side. This difference in pull, or tidal force, is what stretches our oceans to create high and low tides. Now, imagine scaling up that gentle stretching force by an almost unimaginable factor. That is what happens in a tidal disruption event.

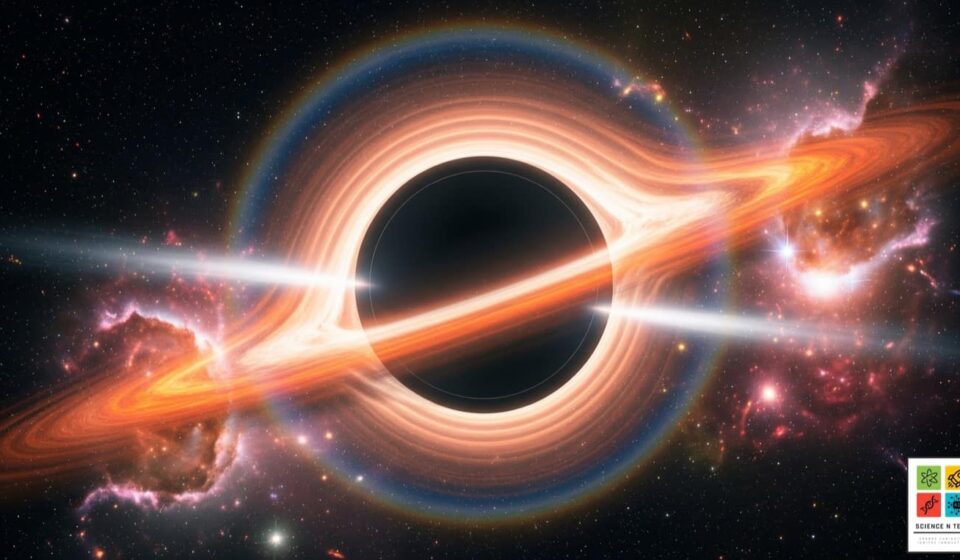

As an unlucky star like the one devoured by HLX-1 wanders within the black hole’s “tidal radius,” the gravitational pull on the side of the star closer to the black hole becomes exponentially stronger than the pull on its far side. This immense differential force overcomes the star’s own gravity, which holds it together. The star is stretched vertically and squeezed horizontally, tearing it apart into a long, thin stream of superheated gas. This gruesome and graphically named process is known as

spaghettification. It is the cosmic equivalent of pulling a piece of taffy until it shreds into filaments.

Not all of this stellar spaghetti falls directly into the black hole’s event horizon. The laws of physics dictate that roughly half of the star’s material is flung away into interstellar space at high speeds. The other half is captured by the black hole’s immense gravity and begins to orbit it, forming a swirling, flat disk of matter known as an accretion disk. This disk is, in essence, the black hole’s dinner plate.

The brilliant flare that our telescopes detect is born from this disk. As the gas spirals inward toward the event horizon, intense friction and gravitational compression heat it to millions of degrees Celsius. For HLX-1, Chandra measured the temperature of this gas to be a staggering 3 million degrees. This superheated plasma glows with incredible intensity, releasing a torrent of energy, particularly in the form of high-energy X-rays. It is crucial to remember that the black hole itself is completely invisible; what we see is the brilliant death cry of the matter it is in the process of consuming.

The observed light curve of the TDE—its rise, peak, and decay—provides a direct, real-time chronicle of this entire process of destruction. The initial sharp rise in brightness seen in the years leading up to 2012 corresponds to the star being spaghettified and the accretion disk forming for the first time. This is the “ignition” phase of the meal. The peak brightness observed in 2012 represents the moment of “peak fallback,” when the densest part of the stellar debris stream finally spirals into the innermost region of the disk, causing the accretion rate to hit its maximum. This is the climax of the feast, generating the most friction and the most light. Finally, the long, predictable decay that has been observed for over a decade since is the direct result of the accretion disk thinning out. As the stellar material is either swallowed by the black hole or dissipated, the fuel runs out, and the “dinner plate” is slowly cleared. This fading glow is the after-dinner mint of a cosmic banquet.

The Bigger Picture: Why We Hunt for Black Hole Leftovers

The dramatic story of HLX-1 is more than just a single, spectacular event. It provides a unique window into some of the biggest questions in cosmology, explaining why astronomers dedicate so much effort to hunting for the leftovers of these cosmic meals.

First and foremost, finding and studying IMBHs like HLX-1 is essential for understanding how the universe builds its largest structures. The discovery provides powerful, tangible evidence for the “hierarchical merger” model of SMBH formation. We can now more confidently imagine the early universe populated with these mid-sized black holes, likely born from the first generations of stars or the collapse of dense star clusters. Over billions of years, these IMBHs would have merged, grown, and sunk to the centers of their host galaxies, gradually building the supermassive giants we see today. Each IMBH found is another piece of the puzzle, confirming the existence of the necessary building blocks.

Furthermore, the “galactic cannibalism” origin story of HLX-1 is a perfect illustration of how galaxies themselves grow and evolve. The universe is not a static place; galaxies are constantly interacting, colliding, and merging. By studying remnant cores like HLX-1, astronomers can piece together the violent history of galaxy formation, learning how large galaxies like NGC 6099 were assembled by devouring their smaller neighbors.

Finally, TDEs serve as extraordinary natural laboratories for probing the laws of physics under conditions that are impossible to create on Earth. The environment just outside a black hole’s event horizon is a realm of warped spacetime and extreme gravity. By observing how matter behaves as it is torn apart and accreted, scientists can test the predictions of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity in its most extreme domain. These events allow us to study the behavior of matter at temperatures and densities far beyond anything we can achieve in a lab, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of fundamental physics.

The hunt is far from over. While the discovery of HLX-1 and a handful of other candidates has been a monumental breakthrough, scientists need to find many more to build a complete picture. The future of this search is incredibly bright. Upcoming facilities, most notably the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, are poised to revolutionize the field. The Rubin Observatory will scan the entire southern sky every few nights with unprecedented depth and sensitivity, promising to turn the current trickle of TDE discoveries into a flood. Instead of finding one or two dozen per year, astronomers anticipate discovering hundreds or even thousands. This wealth of data will allow for the first time a statistical study of IMBHs, helping us to finally understand their populations, their origins, and their ultimate role in shaping the cosmos we see today.

References

- Astronomy Staff. (2023, May 18). New class of black holes discovered. Astronomy.com. https://www.astronomy.com/science/new-class-of-black-holes-discovered/

- Baker, H. (2025, July 31). See the universe’s rarest type of black hole slurp up a star in stunning animation. Live Science. https://www.livescience.com/space/black-holes/see-the-universes-rarest-type-of-black-hole-slurp-up-a-star-in-stunning-animation

- Chandra X-ray Observatory. (n.d.). Learn About Black Holes. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://chandra.harvard.edu/learn_bh.html

- Chandra X-ray Observatory. (n.d.). Tidal Disruption Events. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://chandra.harvard.edu/tdamm/

- Chandra X-ray Observatory. (2017, February). A Likely Decade Long Black Hole Tidal Disruption Event. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://chandra.harvard.edu/graphics/resources/ppt/ss_highlights/2017/Feb-17.pdf

- Chandra X-ray Observatory. (2025, July 24). NASA’s Hubble, Chandra Spot Rare Type of Black Hole Eating a Star. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://chandra.harvard.edu/photo/2025/ngc6099/

- Cooper, K. (2025, July 25). Rogue black hole found terrorizing unfortunate star in distant galaxy. Space.com. https://www.space.com/astronomy/black-holes/rogue-black-hole-found-terrorizing-unfortunate-star-in-distant-galaxy

- CrashCourse. (2015, October 15). Black Holes: Crash Course Astronomy #33 [Video]. YouTube.(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZWPBKULkdQ)

- Daily Mail. (2025, August 3). Chandra discovers giant black hole destroying a star [Video]. Dailymotion. https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x9o898m

- European Space Agency. (n.d.). Black holes.(https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Black_holes)

- European Space Agency. (n.d.). Speeding black hole.(https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Extreme_space/Speeding_black_hole)

- European Space Agency. (2009, July 1). XMM-Newton discovers a new class of black holes.(https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/XMM-Newton_discovers_a_new_class_of_black_holes)

- European Space Agency. (2012, March 19). ESA/ESO Exercise 6: The Black Hole at the Centre of the Milky Way. https://www.eso.org/public/products/education/edu_0061/

- European Space Agency. (2013, April 2). Black hole wakes up and has a light snack.(https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Black_hole_wakes_up_and_has_a_light_snack)

- European Space Agency / Hubble. (2012, February 15). Hubble finds relic of a shredded galaxy. https://esahubble.org/news/heic1203/

- European Space Agency / Hubble. (2023, May 23). Hubble hunts for intermediate-sized black hole close to home. https://esahubble.org/news/heic2306/

- European Space Agency / Hubble. (2025, May 8). Hubble observes new tidal disruption event (January 2025 image). https://esahubble.org/images/opo2515/

- EurekAlert!. (2009, July 1). New class of black holes discovered. https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/735143

- Godet, O., et al. (2017). The one-year recurrence of the quasi-periodic outbursts of the intermediate-mass black hole HLX-1 is gone. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 469(1), 886–897. https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/469/1/886/3586654

- Harker, J. (2025, August 3). Incredible animation shows the moment extremely rare black hole rips apart star in explosion. LADbible. https://www.ladbible.com/news/science/animation-black-hole-star-explosion-151513-20250803

- KIPAC. (2017, June 29). Discover our Universe: Black Holes with Dan Wilkins [Video]. YouTube.(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mafIbWwk4BE)

- Lin, D., et al. (2018). A likely decade-long sustained tidal disruption event. Nature Astronomy, 2, 656–661. https://scitechdaily.com/chandra-reveals-a-decade-long-sustained-tidal-disruption-event/

- Miller-Jones, J. (2015, October 22). How a black hole swallows a star. University of California. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/how-black-hole-swallows-star

- NASA. (n.d.). Black Holes. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/universe/black-holes/

- NASA. (n.d.). Black Hole Types. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/universe/black-holes/types/

- NASA. (n.d.). What Are Black Holes?. https://www.nasa.gov/universe/what-are-black-holes/

- NASA. (n.d.). What Is a Black Hole? (Grades K-4). https://www.nasa.gov/learning-resources/for-kids-and-students/what-is-a-black-hole-grades-k-4/

- NASA. (n.d.). What Is a Black Hole? (Grades 5-8). https://www.nasa.gov/learning-resources/for-kids-and-students/what-is-a-black-hole-grades-5-8/

- NASA. (2015, October 21). Tidal Disruption. https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/tidal-disruption/

- NASA. (2025, July 24). HLX-1 Animation. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/asset/hubble/hlx-1-animation/

- NASA. (2025, July 24). HLX-1 Illustration. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/asset/hubble/hlx-1-illustration/

- NASA. (2025, July 24). NASA’s Hubble, Chandra Spot Rare Type of Black Hole Eating a Star. NASA Science. https://science.nasa.gov/missions/hubble/nasas-hubble-chandra-spot-rare-type-of-black-hole-eating-a-star/

- NASA Goddard. (2025, July 24). NASA’s Hubble, Chandra Spot Rare Type of Black Hole Eating a Star. https://science.gsfc.nasa.gov/sci/pressreleases

- NASA, & Rowan University. (n.d.). Black Holes Educator Guide. https://sites.rowan.edu/planetarium/_docs/black-holes-educator-guide_nasa.pdf

- Outschool. (n.d.). Black Holes, Unusual Galaxies and Other Special Topics in Astronomy! (Weekly).(https://outschool.com/classes/black-holes-unusual-galaxies-and-other-special-topics-in-astronomy-weekly-JROtCfkJ)

- Parshley, L. (2025, July 25). Scientists Spot an Exceptionally Rare Intermediate Black Hole Eating a Star. PetaPixel. https://petapixel.com/2025/07/25/scientists-spot-an-exceptionally-rare-intermediate-black-hole-eating-a-star/

- Starlust. (2025, April 11). Watch one of the universe’s elusive black holes gravitationally tearing apart a star in a burst of radiation. https://starlust.org/watch-one-of-the-universes-elusive-black-holes-gravitationally-tearing-apart-a-star-in-a-burst-of-radiation/

- STScI. (2025, July 24). HLX-1 Animation [Video].(https://www.stsci.edu/contents/media/videos/2025/016/01K0SP1KQQB9HQB6W4CWAWX0T7)

- Syracuse University News. (2024, February 1). Tidal Disruption Events and What They Can Reveal About Black Holes and Stars in Distant Galaxies. https://news.syr.edu/blog/2024/02/01/tidal-disruption-events-and-what-they-can-reveal-about-black-holes-and-stars-in-distant-galaxies/

- The Transients. (n.d.). Tidal Disruption Events (TDEs). https://www.transients.science/tidal-disruption-events

- Todd, I. (2025, July 25). A very rare kind of black hole has been discovered by astronomers, and it’s devouring a nearby star. BBC Sky at Night Magazine. https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/news/ngc-6099-hlx-1-tidal-disruption-event

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). HLX-1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HLX-1

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Tidal disruption event.(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tidal_disruption_event)

- YouTube. (n.d.). HLX-1 Animation — Intermediate-Mass Black Hole Captures and Shreds Star — Hubble.(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7SlqDNrhF4)