Walk through any city or look at any coastline, and you’ll see it: the indelible footprint of our modern world, stamped in plastic. Water bottles, shopping bags, food containers—these materials are designed to last forever, and that is both their greatest strength and our planet’s greatest curse. But what if nature, faced with this alien material for less than a century, is already evolving a response? In a startling discovery that feels like science fiction, researchers have found bacteria that are doing the unthinkable: they are eating our plastic waste. This is the strange case of nature’s newest cleanup crew, a microbial army that could revolutionize how we deal with pollution.

Table Of Content

The Discovery in the Dumpster: Meet Ideonella sakaiensis

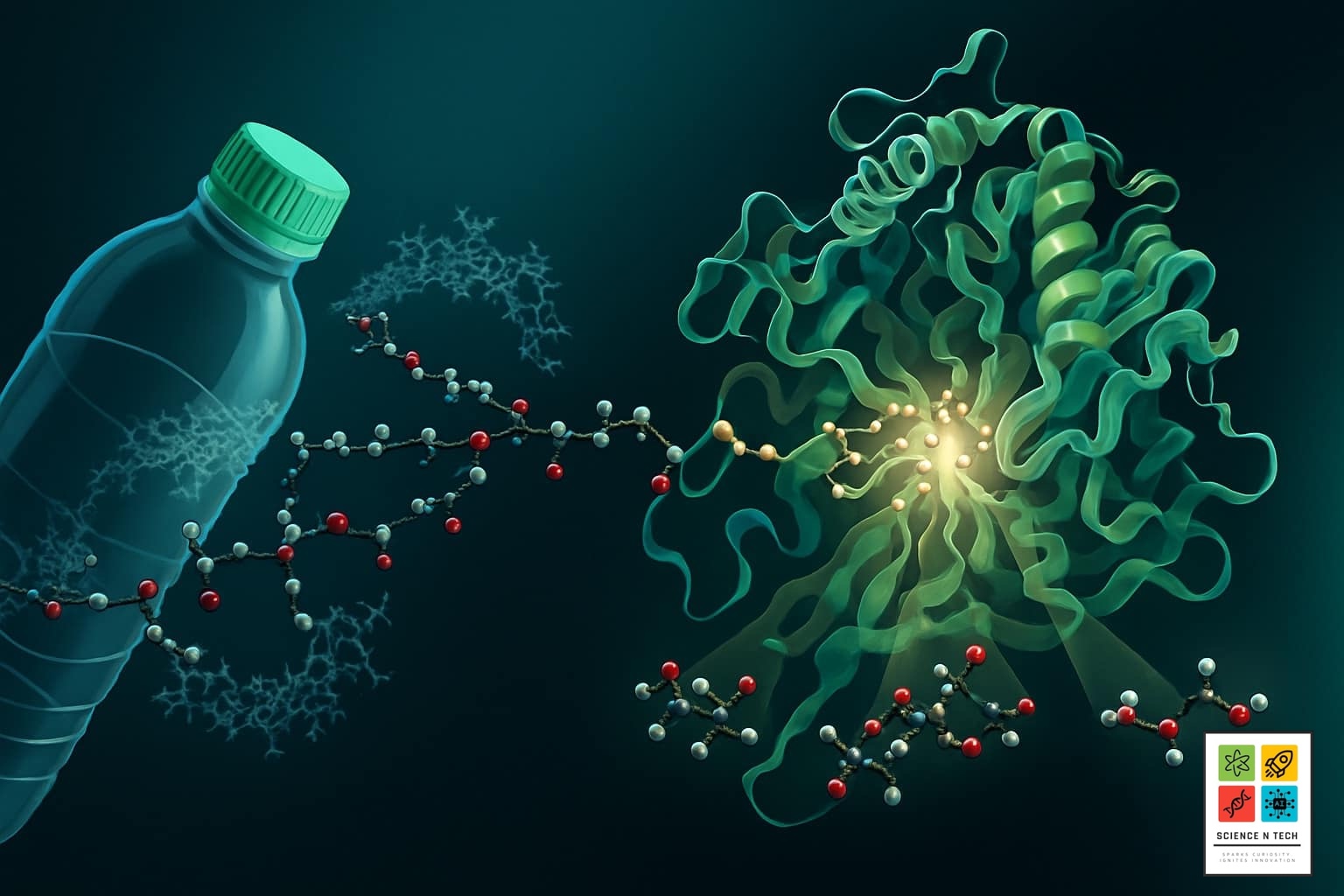

The story begins in 2016, not in a pristine laboratory, but in the grime outside a plastic bottle recycling plant in Sakai, Japan. A team of scientists was sifting through sediment, hunting for microbes that might be interacting with the plastic waste. There, they isolated a new species of bacterium, which they named Ideonella sakaiensis. Under the microscope, they witnessed something extraordinary. This tiny organism was using plastic as its primary food source.

Specifically, it was consuming Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), the ubiquitous plastic used to make single-use drink bottles. The bacterium had evolved a unique two-step process to do this. It secretes a special enzyme, now called PETase, which acts like a first-stage chemical scissors, breaking down the tough polymer surface of the plastic into smaller, manageable molecules (a monomer called MHET). Then, a second enzyme, MHETase, pulls these molecules inside the cell and breaks them down further into their basic chemical building blocks. The bacterium could then use these building blocks for energy and growth.

This was a landmark discovery. It was the first time an organism had been found that could completely break down and metabolize PET plastic. It was as if, in the 70-odd years since plastic became common, nature had already evolved a specific “knife and fork” to consume it.

A Global Army of Microbes is Evolving

For a time, Ideonella sakaiensis seemed like a fascinating fluke. But scientists soon realized it was just the first sign of a global evolutionary event. By searching through huge genetic databases from environmental samples, researchers have now identified hundreds of other potential plastic-degrading enzymes in microbes from all over the world, from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains.

This isn’t limited to just bacteria or just PET plastic. Researchers have found:

- A soil fungus, Aspergillus tubingensis, which can break down polyurethane (PU), a plastic commonly used in adhesives, foam, and insulation.

- The gut bacteria inside mealworms and wax worms have been shown to degrade polystyrene (Styrofoam), one of the most notoriously difficult plastics to recycle.

- Other microbes that show potential for breaking down different types of polymers, suggesting nature is mounting a multi-pronged attack on our waste.

A surprising fact: This evolution is happening at astonishing speed. Life has been dealing with materials like wood and cellulose for billions of years. Plastic has only been mass-produced for about 70 years. For microbes to have developed entirely new enzymatic pathways to digest this synthetic material in such a tiny evolutionary window is a stunning testament to the adaptability of life. Scientists now refer to the ecosystem of microbes living on floating plastic debris as the “Plastisphere,” a new man-made habitat that is serving as a hotbed for this rapid evolution.

From Lab Bench to Landfill: Can We Supercharge These Microbes?

While this is incredibly exciting, we can’t simply release these bacteria into our oceans and landfills and expect them to clean up our mess. The natural process is extremely slow, and the environmental conditions are far from optimal. The real solution lies in harnessing their power and putting it on steroids.

This is where biotechnology comes in. Scientists are now using protein engineering to create “super-enzymes.” They take the naturally occurring PETase enzyme and use AI and lab techniques to introduce mutations that make it far more effective. In 2020, a team created an enzyme that could break down plastic six times faster than the 2016 version.

The French company Carbios is already commercializing this. They have developed an engineered enzyme that can operate at high temperatures, allowing it to break down 90% of a PET bottle into its constituent parts in just 10 hours. This is the ultimate goal: biological recycling. Instead of melting plastic down (which degrades its quality), we can use these enzymes in large bioreactors to chemically de-polymerize our waste. This process breaks plastic down to its pure, original chemical building blocks, which can then be used to create new, virgin-quality plastic over and over again, creating a truly circular economy.

Another little-known fact: One of the first “super-enzyme” breakthroughs was a partial accident. In 2018, scientists were studying the original PETase enzyme and made a mutation to better understand its structure. They inadvertently created a version that was 20% more efficient at degrading plastic, kicking off the global race to intentionally engineer even faster and more robust enzymes.

Nature is showing us a way out of the plastic crisis by evolving a solution in real-time. While these microbes are not a license to continue polluting, they represent a powerful new tool in our arsenal. As we learn to harness and accelerate this natural process, are we witnessing the dawn of biological recycling, and can we deploy it fast enough to clean up the mess we’ve made?

References

- Yoshida, S., Hiraga, K., Takehana, T., et al. (2016). A bacterium that degrades and assimilates poly(ethylene terephthalate). Science, 351(6278), 1196-1199.

- Austin, H. P., Allen, M. D., Donohoe, B. S., et al. (2018). Characterization and engineering of a plastic-degrading aromatic polyesterase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(19), E4350-E4357.

- Carbios. (n.d.). A REVOLUTIONARY ENZYME AT THE HEART OF OUR PROCESSES. Company Website.

- Greshko, M. (2020, October 13). ‘Super-enzyme’ discovery is another leap forward for recycling plastic. National Geographic.

- Gewert, B., Plassmann, M. M., & MacLeod, M. (2015). The “Plastisphere” – A new marine ecological niche. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 2(12), 317.